Karen

Whitman

at

the Woodstock Artists Association

By

RAYMOND J. STEINER

ART TIMES Jan/Feb 2006

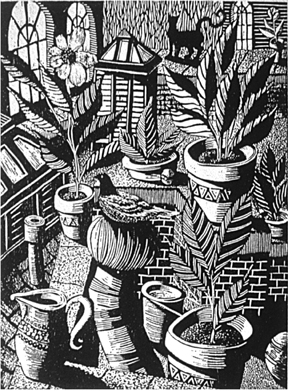

SOME THIRTY-FIVE prints — primarily linoleum cuts,

but two etchings (“Brooklyn Bridge-Pearl St.” and “Columbus Circle”) and

one woodcut (“Rooftop Garden”, my particular favorite in the exhibit,

incidentally) are included — by master printmaker Karen Whitman

comprise the present show* at the Woodstock Artists Association and, for

the aficionado of black-and-white art, this is a show you won’t want to

miss. I confess to my own long-standing preference for black and white

and explain (if not excuse) the bias on the basis of an inherent weakness.

Simply put, color easily seduces me. Consequently, even a mediocre colorist

can sometimes trick me into believing that I am in the presence of genuine

talent. Black and white, on the other hand, tends to fine-tune my critical

faculties, and I have a much easier job of focusing on line, form, pattern,

and over-all composition — in other words the art of the

art. Color is emotionally perceived; black and white, intellectually (and,

as I believe, ‘critically’).

That said, let’s turn to Whitman’s work. Perhaps I should

first point out that there are indeed a number of colored linoleum cuts

— less than a dozen — in the exhibit but, relatively speaking,

few enough in number not to distract from the overall impression of “New

Light on New York” being primarily a “black and white” show and therefore

subject to my (arbitrary) terms of evaluation. I might also add at this

point that, in spite of my prejudice, I found two of these colored linoleum

cuts visually compelling: “Dakota Chimneys” and “Painting the Town”.

As the title of the show suggests (as well as the few

examples I’ve so far mentioned), the theme of the exhibit is New York

City with an emphasis on Whitman’s unique impression of this often hackneyed

cityscape. Indeed, it is Whitman’s vision that initially impacts on the

viewer’s impression upon first entering the gallery — and it is

only upon noting the labels (and, of course, knowing the title of the

show) that we appreciate the fact that we are viewing a particular city.

For all intents and purposes, however, Whitman’s world is a peculiarly

nondescript (if highly personal) one. Given a few moments of browsing,

Brooklyn- and Manhattanites will almost surely recognize such broader

vistas as “Fantasia on Brooklyn” and “Midtown Mambo” as “hometown” sights.

However, the smaller-scaled works such as “Day’s End”, “Airshaft”, “Catwalk”,

“Glow”, “Lamplight”, “Nightfall”, “Red Eye” “Towers”, or “Village Lights”

though obviously city vignettes, might be common views of any city at

all.

And,

herein, I believe lies the central power of the show.

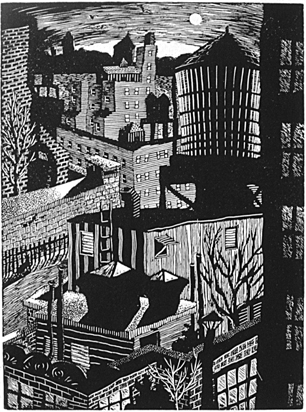

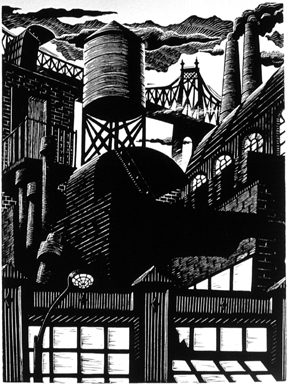

This is not a simple depiction of a particular cityscape — titles and labels indicating otherwise notwithstanding — but rather a journey into Karen Whitman’s city — a city of haunting quiet, vertiginous descents, skewed viewpoints, odd corners, and a pot-pourri of picaresque windows, dormers, and façades. It is a city carefully chosen by a distinctly individual sensibility that not only discloses a special familiarity with it, but also reveals insights into its secrets. Although an occasional person is caught in passing, or a cat spied on a windowsill, or even a passenger-filled airplane in flight overhead, Whitman’s city is a city of inanimate things — high risers, water tanks, bridges, doorways, smog-spewing smokestacks, building fronts, signs, houses, rooftops, and firehouses. Teeming with the signs of human habitation and influence, there is little life in Whitman’s world. At bottom, it is a city that, in spite of its “rooftop garden” or quaint building ornament, is a city of foreboding gloom. Even the trees are leafless.

I do not use “comic book” in any derogatory sense here.

Of course I grew up on comics, but I’ve long felt that they’ve suffered

short shrift when viewed as art. After all, how are comic book bulked-up

heroes essentially different from Michelangelo’s muscle-bound men up on

the Sistine Chapel? In any case, apropos the print, there is only a difference

in degree (and supposedly in intent) between the line drawing of a woodcut

and that of the comic strip. The early woodcut — as Whitman is so

clearly aware — was particularly suited to clear and concise expression.

And, like such early masters as Schongauer and Dürer, she deftly capitalizes

on the compelling potency of strong line combined with light and dark

patterns. Used skillfully, black and white — though I’ve suggested

differently above — can be emotionally — at times explosively

— evocative, though most often in the service of the “dark” side

of human consciousness — another thing those early printmakers knew,

who often employed the medium to scare sinners into right living. In “New

Light on New York” Whitman’s masterful draftsmanship — especially

when she “plays” with perspective, angle of viewpoint, purposeful distortion,

and suggestive mood — is “telling a story” in much the same fashion

as we would find in the comic strip or book. Taken as a whole, with the

exception of very few of the images in this show, the exhibit can well

be “read” as a “story” with New York City as the “main character”.

That “New Light on New York” need not be viewed

as a tale of New York, however, highlights Whitman’s genius as an artist.

Any one of these images can not only be taken “out of context”, but practically

demands that we do so. Viewed separately, taken on their own terms, each

is a completely realized and unified work of art. Oddly, when we do so,

much of the “doom and gloom” that I (and let’s be clear that it is

only my own interpretation) am reading into the show disappears. Thus,

toppling buildings and twisted stovepipes mysteriously lose their sinister

aspects to become mere pictures of whimsical fancy.

By any standard, Karen Whitman’s is a very special talent

and this show a powerful testament to her unique vision. Her art piques,

surprises, enchants, puzzles, and delights. One can ask for little more

from an artist.

*“Karen Whitman: New Light on New York—Linoleum

Block Prints” (thru Jan 8, ’06): Woodstock Artists Association, 28 Tinker

St., Woodstock, NY (845) 679-2940.